Currently, artists are experiencing real injustice and feel powerless or resigned regarding their remuneration or the lack of remuneration from streaming. Despite broadcasts on online platforms, they receive little or nothing for this exploitation of their music.

In fact, non-featured performers never receive royalties for the on-demand streaming* of the music in which they participate.

While recorded music is presently mainly consumed online, Artisti wants to ensure that the remuneration of performers linked to these exploitations of their music is fairer and, above all, that it reaches their pocket…

while they are the reason why users subscribe to the platforms in the first place, the performers are the last link in the payment chain and the money coming from on-demand streaming does not trickle down to them or very little (if they are featured performers only).

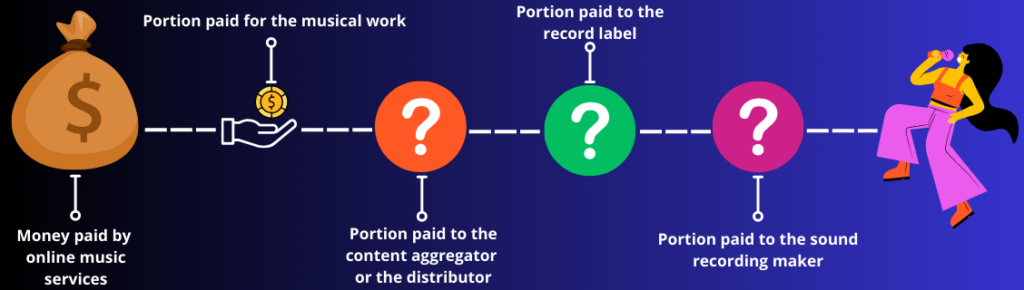

Indeed, on the money path that should lead to performers, several intermediaries (aggregators or digital distributors, labels, makers) take a share, leaving little or nothing when payment reaches the performers. In the case of songwriters, the situation is very different since the amounts deriving from streaming go directly from the platforms to their collective management organization, which, in turn, redistributes the royalties to them: no middleman take his share before them.

It is difficult to know the amounts that are collected, kept and paid at each level and the performers are often clueless when it comes to determining how much they should receive for the streaming of their music.

In addition, the value of a single stream is difficult to assess for them as the variables taken into consideration are vague and/or the data are confidential.

The fact that the platforms prorate the overall sums to be distributed based on the number of streams obtained by each piece of music rather than using a model considering what is listened to by each subscriber (so-called “user-centric” model) was also pointed as being problematic. The same goes for whether a song pushed by an algorithm should receive the same amount as a song that a listener has specifically chosen to stream.

Since they do not have a record deal providing for the payment of royalties for this form of streaming, non featured performers are only paid for the recording session but do not receive royalties when their music is streamed on demand, even if the sound recording in which they participate is very successful and generates millions of on-demand streams and their contribution to this success is undeniable.

The SOLUTION lies in MOBILIZATION for the government to ACT and MODIFY the Canadian Copyright Act.

Streaming royalties are a LEGITIMATE source of revenue for performers and it is time for the Canadian government to protect them.

Artists must massively SUPPORT Artisti’s demands, answer to its call for action and DENOUNCE the injustice of the situation.

This claim is echoed by the mobilization movements that have formed in several countries, all denouncing that the money from music streaming does not end up in the performers’ hands.

This campaign was launched in April 2020 by Tom Gray, musician, and member of the rock band Gomez, to express the dissatisfaction of music creators with the streaming business model and ask for a fairer compensation.

The campaign mobilized a very large number of artists, including several who are well-known. The sustained claims of the performers attracted the attention of the British government, which began work in 2021 to better understand the equity issues related to the remuneration of creators and performers in relation to streaming. The Committee for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport then launched an Inquiry on the Streaming Economy. Among the key recommendations is a call for the UK government to introduce a right to some form of fair remuneration that would increase performers’ royalty payments.

In June 2022, Kevin Brennan, Member of the UK Parliament, introduced a bill in the House of Commons entitled ‘Copyright (Rights and Remuneration of Musicians, Etc.),’ which is currently in second reading.

This petition launched by the Belgian collective management organization Playright Music and which was massively supported by Belgian artists asked the federal government to better protect their rights for the digital distribution of their performances – under the threat that they would otherwise have no other choice but to move to Spain – a rare country where there is specific remuneration for the exploitation of performers’ performances online.

Thus, on August 1, 2022, a law came into force requiring platforms to enter into license agreements with the holders of the rights to the content posted online. This new law introduces a new right for performers i.e, an unwaivable right to remuneration subject to mandatory collective management for the use of their performances on online content-sharing platforms (Facebook, YouTube etc.) and streaming platforms (Spotify, Apple Music etc).

In February 2023, Spotify and the three majors (Universal, Sony and Warner) filed an appeal to have the law voided.

WIPO: is a United Nations agency comprising 193 Member States. It is responsible for promoting Intellectual Property (patents, copyrights, trademarks, etc.) throughout the world as well as monitoring the 23 international treaties in this area – including the conventions that aim to guarantee artists royalties on their performances and fair compensation.

In March 2023, WIPO devoted an information session dedicated specifically to the Music Streaming Market.

Invited by WIPO, Artisti was present at this information session and participated in a panel during which it explained the role of collective management organization have in relation to the streaming of music in a context where performers receive little or nothing from the streaming of their music.

Various international organizations including AEPO ARTIS (an organization bringing together European collective management organizations for performers), FILAIE (Federación Ibero-latinoamericana de Artistas Intérpretes y Ejecutantes), FIM (the International Federation of Musicians) and SCAPR (a global organization bringing together collective management organizations of performers from all over the world) were present at WIPO during this information session and took the opportunity of this special session to hold a side event entitled Unfair remuneration for performers which spoke specifically of this unfair situation in which performers find themselves in relation to the remuneration derived from the streaming of their music.

Currently dominating the music industry, streaming accounts for a significant portion of global music revenue. However, “this success” is far from benefiting performers who derive little or nothing from it.

In 2021, as the music industry experienced the crisis linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, Spotify’s market value tripled to reach $66.9 billion. According to more recent figures published by the IFPI (International Federation of the Phonographic Industry), in March 2023

the global music market is in its 8th consecutive year of growth. However, the main driver of this growth is subscription to streaming platforms. In 2022, there were 589 million paid streaming users, leading to a 9% increase in global recorded music revenue to $26.2 billion.

Given these numbers, the IMBALANCE in relation to what the performer receives is increasingly evident and difficult to justify. It is the artists who create this wealth but who receive little or nothing from the profits that are generated.

FALSE: It is true that for several years now, performers have abandoned the original sound recording production model (under which a maker produces the sound recording) in favor of self-production where they produce their own sound recordings and then licence them to a label to commercialize them.

In these cases, the performer wears two hats: a maker one and a performer one.

In both the original model and the new model of self-production, it is always with the maker of the sound recording that the labels have a business relationship. Thus, when the record companies share up to 50% of the monies received from the distributor, it is to the maker of the recording that they pay them – even if this maker can, in fact, also wear the hat of the performer.

In the original production model, when the sound recording makers receive monies from the label (or directly from the aggregator/distributor when they act both as maker and label), they offset their production costs before starting to pay royalties to the featured performer. Why would things be different in the self-production model? It is not because the performers are self-released artist that the monies paid to them by the labels should automatically be considered as “performers royalties”. If the practice of offsetting one’s production costs is claimed by conventional makers to be a legitimate practice, why should it be otherwise in the self-production model?

Therefore, it is wrong to say that labels pay up to 50% of the sums they receive from distributors to performers! They pay them to the maker of the sound recording who is more and more often also a performer. Therefore, it is only once the self-producers’ production costs have been offset that the payment of their “performer” royalties begins, which would be latter on in the process or never.

Saying that the performers receive often up to 50% of the revenues deriving from the on-demand streaming of their music is therefore not true. It is only in relation to semi-interactive and non interactive streaming that performers get 50% of the royalty share and this is because it is specified in the Copyright Act.

FALSE: In the original production model, featured artists as well receive payment for the recording session. This is what is provided for in the collective agreements in force in the sound recording sector in Quebec. However, this recording session fee payment does not prevent featured performers from collecting royalties as well. Why should it be different for accompanying performers?

Accompanying performers receive their fair share of what is called equitable remuneration royalties (in relation to the non interactive and semi-interactive streaming of their music) and the same should apply to all online exploitations of their musical performances.

While it is generally accepted that the share of equitable remuneration royalties going to accompanying artists is generally less than the one of featured artists, the fact remains that accompanying artists contribute to the success of the sound recordings in which they participate and that they should therefore receive royalties for any online exploitation of their performances, including on-demand streaming.

FALSE: How could accompanying performers who receive nothing from the on-demand streaming of the sound recordings in which they participate receive less? From the outset, this statement is false for many performers!

In addition, Will Page the former chief economist of Spotify released a study entitled “Equitable remuneration: Policy Options and their Unintended Consequences” in which he analyzes the Spanish model under which platforms pay 2.4% of their gross income to Spanish collective management organization for performers called AIE and he has demonstrated that such a model resulted in a 13% increase in streaming revenue for performers (including accompanying ones).

The only way in which performers’ incomes could decrease is if we take for given that the share of accompanying performers should be deducted from the share of featured performers rather than providing that the other links in the payment chain or the platforms themselves should pay for it (or decrease their portion of royalties) to allow accompanying performers to receive their fair share.

In short, it is wrong to claim that all models that would result in direct payment from platforms to performers’ collective management organizations in connection with on-demand streaming would result in a decrease in the share reaching performers. The wrongness of this assertion is particularly obvious when one considers the interest of the accompanying performers whose share cannot decline since they currently receive nothing for on-demand streaming.

FALSE: While it is true that sound recordings could in some cases see their share of the pie increase with a user-centric distribution model, this will not solve the problem of the distribution of monies between the different stakeholders in the chain of payment and will not result in more monies reaching the performers’ hands.

The only way to ensure that monies reach performers (in their capacity as performers and not as self-producers of their sound recordings) is to ensure that royalty payments specifically intended for them are made by the platforms directly to their collecting management organizations.

That said if the platforms also adopt, in parallel, a user-centric distribution model which would result in some sound recordings being awarded a larger share of the pie then it is actually the case, then this would only improve the payments to performers participating in these sound recordings.

FALSE: An impressive number of performers whose music is widely played on streaming platforms do not receive any royalties or absolutely ridiculous sums for the streaming of their music..

Among these are non-featured /accompanying performers who never receive royalties for on demand streaming of their music, but also the featured performers to whom the monies simply do not trickle down, being held up by the other links of the payment chain.

FALSE: Some of the largest online music platforms do not pay equitable remuneration royalties that they should pay pretexting that all uses they make of music are already covered by the licenses they obtain, which is wrong.

Indeed, the only way to legally obtain a license for non-interactive and semi-interactive streaming in Canada is to obtain it from the sole Canadian collecting society that is designated to issue licenses and collect all royalties related to these forms of streaming, i.e. ReSound. If the platform claims to have obtained a license allowing it to do non-interactive and semi-interactive streaming from another entity than ReSound, this claim is illegitimate.

Finally, some platforms claim they only offer on-demand streaming even if they push content to their premium and freemium subscribers and:

By claiming they only offer on-demand streaming, they avoid paying equitable remuneration while some of their streaming activities should be subject to the payment of equitable remuneration royalties.

Form of streaming where the members of the public cannot instantly access a chosen sound recording on the device of their choice. With non-interactive: or semi-interactive streaming, the members of the public will be able to listen to sound recordings or playlists that will be pushed to them by the platform but will not be able to stream the exact sound recording they are asking for, to play a song that they like for a second consecutive time and to skip as many tracks they want to skip. Furthermore, this kind of streaming is subject to the broadcasting of advertisements from time to time.

These forms of streaming are mainly found on the free version of Spotify or on IheartRadio or Stingray Music.

Form of streaming where the members of the public can instantly listen to the specific sound recording they choose, on the device of their choice. This form of streaming is available to paying subscribers of Spotify Premium; Apple Music; Deezer; Google Play.

A model where the global pool of royalties is divided between the total number of streams, in such a way that a sound recording that attracted a lot of streams will receive much more than a sound recording that has attracted less plays. Under this system the subscription fee paid by a a does not flow strictly to the performers performing on the music that was streamed by this subscriber.

Spokesperson for the European collective management organizations of performers. This association regroups 38 organizations established in 28 different countries and representing more than 650,000 performers of the musical and audiovisual sector. Very active in the protection of the rights of performers, AEPO ARTIS campaigns in favor of a fairer remuneration for performers for the streaming of their music, administered by collective management organizations of performers. Website

Federación Ibero-latinoamericana de Artistas Intérpretes y Ejecutantes. Founded in 1981, the Federation represents more than 300,000 performers from 17 countries through 20 collective management organizations. Its mission: to safeguard the artistic and heritage interests of Latin American performers.

International Federation of Musicians. Founded in 1948, is the international organisation for musicians’ unions and their equivalent.. It represents 70 members in 60 countries throughout the world. The Federation’s main objective is to protect and further the economic, social and artistic interests of musicians represented by its member unions.

Notre site web utilise des témoins de navigation (cookies) et d’autres technologies de suivi pour améliorer votre expérience de navigation et enregistrer vos préférences, ainsi que suivre votre utilisation. En acceptant, vous donnez votre consentement, conformément à notre politique de confidentialité. / Our website uses cookies and other tracking technologies to enhance your browsing experience and save your preferences, as well as track your usage. By accepting, you give your consent in accordance with our privacy policy.